On 5 December 2025, the Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam College (MLC) of the University of Macau held the themed activity “Forging the Heart through Aesthetic Education – Bamboo-Resonance Sketching” in the college library and at “Millennium Ruby Square.” Using the cultural connotations of bamboo as the point of starting for artistic sketching practice, the event enabled students to experience the charm of art and to enhance their cultural understanding and skills.

The event proceeded in an organized manner in the format of “lecture + sketching (from life).” The College Resident Tutor Huang Ronghui first delivered a themed talk in the College library titled “Forging the Heart through Aesthetic Education – Bamboo-resonance Sketching”. She explained the spiritual qualities of integrity and resilience embodied by bamboo, one of the Chinese traditional “Four Gentlemen.”

No Home Without Bamboo: Bamboo in the Cultural ImaginationThe lecture began with the historical connections between bamboo and China, explaining the importance of bamboo in people’s daily lives in ancient times, and further helping students appreciate the deeper cultural meaning in Su Shi’s line, “Better to go without meat than to live without bamboo.” The talk also presented poems and paintings by Chinese artists of various dynasties that personify bamboo, showing how literati expressed their inner feelings and noble character through writing, praising, and depicting bamboo. Since Su Shi, the literary status of bamboo has risen to an unprecedented height. In the essay “Record of Wen Yuke’s Painting of Prostrate Bamboo in Yundang Valley,” which he wrote for his close friend Wen Tong, the well-known idiom “xiong you cheng zhu” originates.In Record of Wen Yuke’s Painting of Prostrate Bamboo in Yundang Valley, Su Shi gave a detailed account of Wen Tong’s ink paintings of bamboo:

“Therefore, to paint bamboo one must first have the complete bamboo in one’s mind. Taking up the brush and gazing intently, one then perceives what one wishes to paint, quickly rises to follow it, and lets the brush sweep straight ahead to pursue what one has seen, like a rabbit suddenly starting and a falcon swooping down—relax for even an instant and it will be gone.”

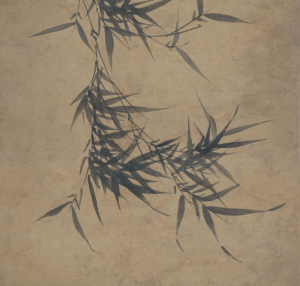

Among painters of successive dynasties, Northern Song artist Wen Tong, Ming-dynasty painter Xia Chang, and Qing-dynasty painter Zheng Banqiao, among others, are renowned in the history of Chinese painting for their depictions of bamboo. Xia Chang is acclaimed as the foremost painter of bamboo in the Ming Dynasty. He excelled at painting bamboo in ink; the leaves he depicted seem to flutter in the wind, their forms rigorous yet still imbued with the “freehand” spirit of Ming painting, fully revealing the artist’s natural insight into bamboo.

Throughout his life, the Qing-dynasty painter Zheng Banqiao took delight in painting bamboo, loved composing verses about it, and blended poetry into his paintings. He planted bamboo in the backyard of his home and named it “Garden of Embraced Green,” which shows just how fond he was of bamboo. Zheng’s bamboo paintings are lively and full of spirit, natural and unaffected; with just a few expressive strokes, the image of bamboo suddenly takes shape. He once wrote a poem titled Bamboo in the Rock to express his understanding of it:

“Upright stands the bamboo amid green mountains steep,

Its toothlike root in broken rock is planted deep.

It’s strong and firm though struck and beaten without rest,

Careless of the wind from north or south; east or west”

(cited from the translation by Xu Yuanchong)

On the surface, this poem is about bamboo, but in fact it conveys Zheng Banqiao’s own noble character—upright, unyielding, and indomitable.

Huang Ronghui’s profound lecture, rich in the aesthetic spirit of Chinese culture, not only helped students understand the cultural significance of bamboo in Chinese tradition, but—more importantly, as an introductory course in Chinese painting—greatly sparked their interest in painting and strengthened their pride in their national culture.

Dancing Brush and Ink: Millennium Ruby Brimming with LifeAfter the lecture, the students went to the College’s Millennium Ruby Square for sketching. During the session, Li Haihao, PhD candidate of UM’s Department of Arts and Design, first explained the basic brush techniques of ink painting: the use of ink tones, and compositional skills for painting bamboo. He demonstrated how to use the side of the brush to paint the bamboo stalks section by section upward, focused on how to outline the upright bearing of bamboo with calligraphic brushwork, and showed how variations in ink density can express the layering of bamboo leaves. Using the “ren” (人), “ge” (个), and “jie” (介) character methods, he explained in simple terms the brush-and-ink structure for painting bamboo leaves. Huang Ronghui and Li Haihao provided roving guidance throughout the session, patiently offering individual feedback on each student’s work. From controlling the proportions of bamboo joints, to arranging the interweaving of branches and leaves, to balancing the interplay of “solid” and “empty” in brush and ink, they gave careful, step-by-step instruction—guiding everyone to infuse the spirit of bamboo into their brushwork. Many students moved from initial unfamiliarity with ink-wash techniques to gradually mastering key skills in handling the brush and using ink. The bamboo they painted began to reveal an increasingly upright, resonant charm. The sketching session was focused and lively, suffused with a quiet, poetic atmosphere.

Dancing Brush and Ink: Millennium Ruby Brimming with LifeAfter the lecture, the students went to the College’s Millennium Ruby Square for sketching. During the session, Li Haihao, PhD candidate of UM’s Department of Arts and Design, first explained the basic brush techniques of ink painting: the use of ink tones, and compositional skills for painting bamboo. He demonstrated how to use the side of the brush to paint the bamboo stalks section by section upward, focused on how to outline the upright bearing of bamboo with calligraphic brushwork, and showed how variations in ink density can express the layering of bamboo leaves. Using the “ren” (人), “ge” (个), and “jie” (介) character methods, he explained in simple terms the brush-and-ink structure for painting bamboo leaves. Huang Ronghui and Li Haihao provided roving guidance throughout the session, patiently offering individual feedback on each student’s work. From controlling the proportions of bamboo joints, to arranging the interweaving of branches and leaves, to balancing the interplay of “solid” and “empty” in brush and ink, they gave careful, step-by-step instruction—guiding everyone to infuse the spirit of bamboo into their brushwork. Many students moved from initial unfamiliarity with ink-wash techniques to gradually mastering key skills in handling the brush and using ink. The bamboo they painted began to reveal an increasingly upright, resonant charm. The sketching session was focused and lively, suffused with a quiet, poetic atmosphere.

As the event drew to a close, students displayed and shared their sketches in the garden area, the college’s Evergreen Dining Hall, and the main lobby. Many remarked that the activity not only deepened their understanding of bamboo’s cultural resonance, but also helped them gain an initial grasp of the fundamental techniques of ink-wash painting. Through on-site observation and brush-and-ink creation, they truly experienced the essence of traditional Chinese aesthetics—“capturing the spirit through form” (以形写神). Their love for and desire to explore traditional art were further inspired, and they also developed a more direct appreciation of the upright and resilient virtues of the junzi (the exemplary person, also gentleman). Students expressed heartfelt thanks to the two instructors for their attentive guidance, and some also shared their hope to continue studying traditional calligraphy and painting and to explore more themes rooted in Chinese culture.

Professor YANG Liu, the College Master, and Dr. Venus Viana, Resident Fellow, attended the session to observe the students’ plein-air sketching practice. Master YANG spoke highly of the students’ works, praising them for their courage to try, keen insight, and outstanding talent. Starting from scratch, the students ventured into the depths of Chinese art and culture, embodying the College’s spirit of refined GRAND BEAUTY and the vitality of Chinese cultural tradition. She expressed the hope that teachers and students would join in shared aspiration and, taking this event as an opportunity, develop more distinctive and elegant art and culture activities.

Yang Qianyu: The Sublimation of Forms

This bamboo-grove sketching activity allowed me, through the interplay of brush and paper, to truly feel how Chinese culture elevates forms in nature into spiritual symbols. By refining the bamboo’s appearance through brush and ink, we were not merely reproducing its natural features—we were also experiencing and conveying the deeper meaning it embodies: humility with integrity, and resilience that never yields.

An Encounter with Excellence

Professor YANG Liu, the College Master, and Dr. Venus Viana, Resident Fellow, attended the session to observe the students’ plein-air sketching practice. Master YANG spoke highly of the students’ works, praising them for their courage to try, keen insight, and outstanding talent. Starting from scratch, the students ventured into the depths of Chinese art and culture, embodying the College’s spirit of refined GRAND BEAUTY and the vitality of Chinese cultural tradition. She expressed the hope that teachers and students would join in shared aspiration and, taking this event as an opportunity, develop more distinctive and elegant art and culture activities.

Yang Qianyu: The Sublimation of Forms

This bamboo-grove sketching activity allowed me, through the interplay of brush and paper, to truly feel how Chinese culture elevates forms in nature into spiritual symbols. By refining the bamboo’s appearance through brush and ink, we were not merely reproducing its natural features—we were also experiencing and conveying the deeper meaning it embodies: humility with integrity, and resilience that never yields.

An Encounter with Excellence “In the tranquil courtyard of Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam College, I tried painting bamboo in ink for the first time. As the wind brushed the bamboo and its shadows rustled, the moment the ink spread across the paper felt truly magical. Although, as a beginner, my brushstrokes were stiff and I could never quite capture the graceful openness of the leaves, watching the bamboo gradually take shape under my brush suddenly made me understand the deeper meaning of the ancient saying ‘xiong you cheng zhu’—to have a fully formed plan in one’s mind before action.This sketching session not only made me fall in love with the charm of ink painting, but also helped me appreciate the bamboo’s resilient and elegant character. I am grateful for this session of painting from life, which allowed me, amid the fragrance of ink, to quietly encounter an ancient quality of character.”

Gao Zihan: Conveying Ideas through Form

“In the tranquil courtyard of Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam College, I tried painting bamboo in ink for the first time. As the wind brushed the bamboo and its shadows rustled, the moment the ink spread across the paper felt truly magical. Although, as a beginner, my brushstrokes were stiff and I could never quite capture the graceful openness of the leaves, watching the bamboo gradually take shape under my brush suddenly made me understand the deeper meaning of the ancient saying ‘xiong you cheng zhu’—to have a fully formed plan in one’s mind before action.This sketching session not only made me fall in love with the charm of ink painting, but also helped me appreciate the bamboo’s resilient and elegant character. I am grateful for this session of painting from life, which allowed me, amid the fragrance of ink, to quietly encounter an ancient quality of character.”

Gao Zihan: Conveying Ideas through Form “Taking part in this ‘Bamboo Resonance Sketching Activity’ allowed me to find a long-lost sense of calm and elegance amid my busy studies. The event began with the cultural lecture ‘Forging Moral Character through the Charm of Bamboo’. In just twenty minutes, it made me rediscover how important bamboo is in the spiritual world of Chinese literati—it is not only a natural object, but also a symbol of integrity, humility and vitality. I came to see that Su Dongpo’s insistence that one ‘cannot live in a place without bamboo’ actually expresses a gentleman’s watch over his spiritual home.The hands-on painting session was especially precious. In the Millennium Ruby Square of the College, with bamboo shadows swaying and birdsong as my companion, I was at first worried because I had no drawing foundation. Yet under the teachers’ guidance, I gradually managed to outline the upright joints of the bamboo and the open, airy leaves. Amid the variations of dark and light ink, I seemed to touch the philosophy of Chinese painting that ‘uses form to convey spirit’—what matters is not painting with photographic realism, but settling one’s mind in the rise and fall of brush and ink.Thank you to the College for organizing an event that so beautifully combined cultural immersion with an artistic experience. It didn’t just teach me how to paint bamboo; it also helped me realize that what aesthetic education truly nourishes is our ability to sense poetry in everyday life and to connect our lives with tradition. I look forward to the College hosting more activities like this—ones that “forge the heart through beauty”—and to creating more wonderful moments together.

Huang Ronghui: The Interplay of the Solid and the Void

“Taking part in this ‘Bamboo Resonance Sketching Activity’ allowed me to find a long-lost sense of calm and elegance amid my busy studies. The event began with the cultural lecture ‘Forging Moral Character through the Charm of Bamboo’. In just twenty minutes, it made me rediscover how important bamboo is in the spiritual world of Chinese literati—it is not only a natural object, but also a symbol of integrity, humility and vitality. I came to see that Su Dongpo’s insistence that one ‘cannot live in a place without bamboo’ actually expresses a gentleman’s watch over his spiritual home.The hands-on painting session was especially precious. In the Millennium Ruby Square of the College, with bamboo shadows swaying and birdsong as my companion, I was at first worried because I had no drawing foundation. Yet under the teachers’ guidance, I gradually managed to outline the upright joints of the bamboo and the open, airy leaves. Amid the variations of dark and light ink, I seemed to touch the philosophy of Chinese painting that ‘uses form to convey spirit’—what matters is not painting with photographic realism, but settling one’s mind in the rise and fall of brush and ink.Thank you to the College for organizing an event that so beautifully combined cultural immersion with an artistic experience. It didn’t just teach me how to paint bamboo; it also helped me realize that what aesthetic education truly nourishes is our ability to sense poetry in everyday life and to connect our lives with tradition. I look forward to the College hosting more activities like this—ones that “forge the heart through beauty”—and to creating more wonderful moments together.

Huang Ronghui: The Interplay of the Solid and the Void This activity not only gave me the opportunity to pass on my artistic training to students, but also led me to develop a new approach to painting myself. In this work I used acrylic paint, whose properties allow a strong sense of volume and three-dimensionality. Using a palette-knife technique, I scraped into and built up the thick layers of paint to form the image of bamboo. From a distance, the picture seems almost empty; up close, however, the texture and mass of the paint reveal the bamboo’s form. This is my own interpretation of the imagery of the “void” and the “solid” in Chinese painting. The entire piece is rendered in pure cinnabar red. Painting bamboo in cinnabar was first pioneered by Su Shi, and it carries auspicious meanings—good fortune, fulfillment, happiness, as well as nobility, purity, and uprightness. For this reason, I chose cinnabar as the dominant element of the composition, as a way to express my deeper understanding of the cultural connotations of bamboo.

Li Haihao: Attain Knowledge by Studying the Nature of Things

This activity not only gave me the opportunity to pass on my artistic training to students, but also led me to develop a new approach to painting myself. In this work I used acrylic paint, whose properties allow a strong sense of volume and three-dimensionality. Using a palette-knife technique, I scraped into and built up the thick layers of paint to form the image of bamboo. From a distance, the picture seems almost empty; up close, however, the texture and mass of the paint reveal the bamboo’s form. This is my own interpretation of the imagery of the “void” and the “solid” in Chinese painting. The entire piece is rendered in pure cinnabar red. Painting bamboo in cinnabar was first pioneered by Su Shi, and it carries auspicious meanings—good fortune, fulfillment, happiness, as well as nobility, purity, and uprightness. For this reason, I chose cinnabar as the dominant element of the composition, as a way to express my deeper understanding of the cultural connotations of bamboo.

Li Haihao: Attain Knowledge by Studying the Nature of Things “This piece was painted from life in the courtyard of Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam College at the University of Macau. It seeks to use traditional Chinese brush-and-ink to express the spirit of the literati, stressing the distillation of the essence of the object rather than mere likeness in form, in keeping with the Song–Ming Neo-Confucian idea of “attaining knowledge by studying the nature of things” (ge wu zhi zhi). I also hope that through this session of sketching and exchange, the students of the College can personally experience the brush-and-ink spirit of Chinese painting and the state of working from life, so that Chinese traditional culture can be better transmitted and promoted.”

After the event, the College displayed the students’ works in the main lobby, the Evergreen Dining Hall, and the garden. As teachers and students passed by, they looked on with admiration. This activity not only engaged students in artistic practice and strengthened cultural participation across the College community, but also enriched the artistic atmosphere of the campus environment: ink-painted bamboo and cinnabar-red bamboo shimmered in mutual harmony with the College’s beautiful surroundings, echoing the charm of “bamboo like strings” and adding an elegant, fresh artistic glow. This was not only an introductory practice in ink sketching, but also a truly intoxicating feast of aesthetics!

“This piece was painted from life in the courtyard of Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam College at the University of Macau. It seeks to use traditional Chinese brush-and-ink to express the spirit of the literati, stressing the distillation of the essence of the object rather than mere likeness in form, in keeping with the Song–Ming Neo-Confucian idea of “attaining knowledge by studying the nature of things” (ge wu zhi zhi). I also hope that through this session of sketching and exchange, the students of the College can personally experience the brush-and-ink spirit of Chinese painting and the state of working from life, so that Chinese traditional culture can be better transmitted and promoted.”

After the event, the College displayed the students’ works in the main lobby, the Evergreen Dining Hall, and the garden. As teachers and students passed by, they looked on with admiration. This activity not only engaged students in artistic practice and strengthened cultural participation across the College community, but also enriched the artistic atmosphere of the campus environment: ink-painted bamboo and cinnabar-red bamboo shimmered in mutual harmony with the College’s beautiful surroundings, echoing the charm of “bamboo like strings” and adding an elegant, fresh artistic glow. This was not only an introductory practice in ink sketching, but also a truly intoxicating feast of aesthetics!

Edit: Roy

Article: Huang Ronghui

Translation: Venus

Proofreading: Rosie

Photos: Brian, Rosie